Social Currency seldom gets measured. Why not? It has the power to build a brand and to empower social change.

Market researchers have traditionally treated the buying public as an aggregate of individuals. Every mainstream statistical routine used in survey analysis does this: so when we see mean scores, medians, top-2 box scores, factor analysis or segmentation work what we’re seeing is the aggregation of individual results followed by some dissection of these numbers.

Yet the buying public is not made up of individuals. Buyers shop for families – and their tastes are shaped as much by the lactose intolerance of their 13 year old daughter as they are by the chit-chat at the Tuesday morning coffee group. We buy according not just to our own tastes, but to the tastes of those around us. Our peers, research consistently shows us, shape the norms around which we operate. Even questions of whether we’re overweight, or smoke are shaped to a considerable degree by what our peer groups view as normal.

For this reason we need a measure of the social index of brands and services. I may love brand X but if my peers are all chatting enthusiastically about brand y, then brand y is more likely to become my choice too.

Social Currency is a name for this measure and as the name implies, there’s a degree of pass-on-value or trade-ability in talking about the brand or service. Right now in the USA Beyonce is enjoying immense social currency – her Mrs Carter tour has been a conversation piece. Have you seen the footage? Did you see that moment when Jay Z crashed the stage? Those outfits. The music. She is worth talking about. Meanwhile Chris Brown is not getting talked about, much, except in a negative way. I cannot imagine anyone starting a conversation with: “have you heard the new Chris Brown song?” But I can imagine a conversation opening with: “You planning to go to the Beyonce concert?” There’s a buzz about her.

Social Currency implies trade-ability, so to measure it we need to know why information or gossip is even traded. Why do we do it? There are several motivations.

- Social currency is a form of social glue. By talking about Beyonce I can join the lunchtime conversation – we have a shortcut to affirming our similarities. I’m one of “us.”

- Social currency affirms our usefulness to our peers. By tipping me off about the latest music release, or about the awful over-sweet taste of the latest confectionery, you prove worth knowing – you affirm your usefulness at least in a symbolic way.

- Social currency may take the form of truly vital information for my community. When Rosa Parks refused to stand up on her bus, word of the incident spread like wildfire through the black communities, and gained traction through the churches. This wasn’t idle gossip – this was a deep social ‘moment’ coursing through the veins of the community.

For these reasons, social currency is relevant to just about everything that market researchers measure. Whether the word of mouth around a product or service, or event, or political scene – social currency is at work whether we measure this or not.

By measuring it we get a picture not just of the aggregate feelings of the market, but a view of how quickly and how dynamic the peer to peer conversations are liable to be. Media analysts in Montgomery Alabama wouldn’t have picked up on the swift undercurrents of dialogue that occurred following Rosa Parks’ arrest on Dec 1st 1955. She was not the first black woman to disobey the bus driver’s ruling on that local bus line – but in this case the grapevine was already running hot.

I’ve seen brands decimated and even destroyed by social currency, and I’ve seen new brands launch spectacularly on the back of viral marketing and word of mouth. Yet I’ve seldom seen social currency used as one of the core measures.

The Rosa Parks story is a fantastic yet simple illustration of how a piece of news spread via word of mouth, not because it was a big story (woman stays seated on bus) but because it was imbued with social importance at the time when racial tensions were close to boiling point. This was a month after a black teenager Emmet Till was murdered for talking to a white girl. It was a case where social currency was much more valuable than media currency or – presumably – the brand values of the Montgomery Bus Company.

I put the blame for this oversight on the shoulders of lazy old-fashioned ‘let’s not rock the boat with innovation’ research companies, lazy ad agencies who talk about currency but dictate the use of bog standard measures such as brand recall (yawn), and I put the blame on marketers and their somewhat limited view (thanks to the universities that train them,) of how humans really operate. This is one bus that researchers don’t sit on, so much as miss completely.

How to find the needle in a haystack of 30 billion lines of straw.

When I was in NYC two years ago the Occupy Wall St movement was in full swing. I wandered to nearby Wall St (the protest was in a park several hundred metres away) and the famous street was being protected by dozens of police mounted on horseback. There were cordons everywhere and brokers rushed from building to building during their lunch hour in what felt palpably like a state of siege. A pretzel cart operated in the heart of the empty street – selling drinks and snacks – and I asked the vendor, an Indian man, how business was going for him. Trading on Wall St, he assured me, was slow.

Still if trading has come down from the record highs set in late 2008, the NYSE still turns over something like 1.5 billion transactions per day, or around 30 billion every month. And somewhere, lurking in those 30 billion lines of data is evidence of insider trading. The question is, how do you find it? The needle is small – the haystack unimaginably big.

The answer is that the SEC is often informed by the investigative team of FiNRA – the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority spearheaded by a man who used to be in the DA’s office: a prosecutor you wouldn’t want on your tail. His name is Cameron Funkhouser, and he’s a big thickset man described by one colleague as an “I can smell a rat, kinda guy.”

But get this – the investigative team he’s put together to delineate all those billions of lines of data, looking for patterns of fraud and insider trading (do two apparent strangers make the same trades on the same days, repeatedly – could they be connected?) this team he’s put together is not chiefly characterised by data geeks and statistical nerds. Heading the unit, underneath Funkhouser’s command is a team spearheaded by:

- Whistle-blower unit – Joe Ozag. (Ex terrorism detective.)

- Anthony Callo – once prosecuted homicides at the DA’s office.

- Laura Gansler – screenwriter and the “brains” of the group.

This team is characterised by diversity, out-of-the-box thinking, and an understanding not so much about statistics as about people: our drives, our motivations and our craftiness: in short; our narratives. Laura Gansler might be the least statistical member of the group – she is an accredited screenwriter and author – but she’s well versed in developing credible storylines and getting inside the head of crooked characters.

And this is the point about dealing with big data. For sure, your programmers and number grunts can dig around and reveal black and white statistical evidence of those occasional insider trading schemes – but the real value in this analysis comes from those who can furnish a credible story and, using logic, suggest where best to look for the telltale finger prints, bloodstains and data trails that mark the crime.

FINRA has proved remarkably effective at helping nail the bad guys, and Funkhouser speaks highly of his team.

The lesson for researchers and business people is that the best way to deal with massive data – 30 billion lines of the stuff every month – is to remember two things.

1) Every bit of data reflects human activity. It isn’t about numbers – it is about people.

2) Get inside the mind of the bad guys – and you know where to look.

Incidentally the FINRA unit reflects, surprisingly closely, the fictitious Department S – the 1970s show that gave us Stewart Sullivan, conventional crime-fighting agent, Annabel Hurst, computer expert, and the redoubtable Jason King, cravat wearing international novelist of mystery. Department S was born of a time when traditional crime (bank jobs and murders) were giving way to global operations. (The French Connection was another movie that wrestled with the same escalation of crime.) So it is interesting that the escalation of data into Big Data should meet with a similar response: put talent and creativity onto the case otherwise there will never be enough resource.

Big fight, wrong context? Coke unleashes their inner Joe Frazier…into the playground.

Society has generally maintained quite tidy divisions between different facets of our lives. Politics and Religion seldom mix, and businesses are generally governed by the free market rather than by Government (save for a regulatory framework, and a a tax regime.) These kingdoms of church, business and state operate by quite different methods and rules.

Increasingly, and in part due to social media, these principalities have begun to collide more frequently. For example advertising media have generally been the domain of business advertisers and these businesses (regardless of their politics, have traditionally steered clear of overt political advertising. They may send money to SuperPacs and lobby groups, but they don’t run adverts that say: “Chevrolet – supporting Obama for a better future.”

But what happens when political lobby groups start targeting business; and do so via those traditional advertising media?

That’s the dilemma that Coca-Cola has been in, in Australia. The issue is rubbish and recycling, and environmental groups and lobbyists have been advocating a real clean-up to the way Australia handles plastic rubbish. What they want is to put a deposit price on plastic bottles, for example, so that these are worth something – and won’t be simply thrown away as litter. After all, plastic litter is causing increasing damage to marine life.

Coca Cola doesn’t want this and advocates a softer option that does not involve their retail price. So game on. Greenpeace put together this advertisement that names and shames the big red lobbyist. It has had around a million views on YouTube and Greenpeace had plans to run the ad on the major Australian networks. See it for yourself.

But none of the networks dared touch the advertisement, and Greenpeace accuse Coke of threatening the networks – using their sizeable ad-spend as leverage. In these days of tighter media budgets, it isn’t easy to plea free speech and watch several million dollars revenue walk out the door. I’ll leave it to you to decide if this is fair practice. Isn’t it just business?

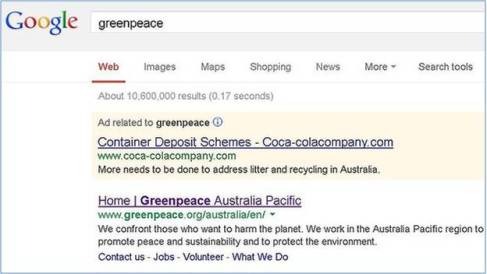

But Coke have gone further – buying (with expensive bids) spots on social media so that every time an Australian looks up Greenpeace , well as you can see in the picture above, an advertised link appears telling the world what a fine option Coca-Colas recycling plan is.

To the news media (See this good piece from the Canberra Times) the actions amount to bullying tactics and the question is raised about the role of corporates once they enter the social media. Can they play by the same rules as they do in the mass media? Who owns this space? Have Google and Facebook commoditised all social space and changed the normal rules of conversation?

These days one might enter a conversation, via Facebook, and wish to talk to like-minded people about recycling. Now you can’t do that, apparently, without a company demanding to enter your face space and intrude in the conversation. It’s like meeting your friends at the cafeteria but then a Jehovah’s Witness joins the party – and starts handing out tracts. Is it acceptable behaviour?

One of the underlying problems is that the different rulebooks that applied to different principalities (church, politics, religion) have gotten blurred because all three kingdoms are claiming legitimate use of the social media. They each play by their own traditional rules – but the result is chaos, friction and conflict. The conviviality of the lunch table has been subverted because others are using it as a platform to do their business. You’ve met with friends, and as if the Jehovah’s witness is not interruption enough, there’s now a sales guy peddling cheap watches, and a political pressure group telling you why we need guns, as well as the loud moron who won’t stop yammering about other stuff altogether.

Social space? Political space? Business space? Which is it?

While the rules evolve and get negotiated (much as the use of mobile phones soon came loaded with some accepted etiquette of do’s and don’ts) we are going to see some ugly scraps. The GreenPeace – Coca Cola stoush has brought out the ugliest side of the beverage firm, and regardless of their environmental politics, they are now coming over as a corporate bully simply because they are applying the law of the advertising jungle to the domain of social media. They have unleashed their inner Joe Frazier, not in the ring, but in the playground.

What planet are they operating on?

Bieber gets booed – what that teaches us about reputation management.

Music awards are warm-hearted events where peers congratulate each other – where country singers get applauded by rap artists, and where R&B stars are lauded by punks. It’s one big family. Music is a generous business. Well usually.

Sure, there was the infamous Brit award ceremony when Jarvis Cocker interrupted Michael (this is for the children) Jackson during the late superstar’s speech. Jackson had forgotten that this was a music award ceremony – and not a Saviour of the World ceremony. But this incident was the excception. By and large musicians are polite.

Not so today when at the Billboard Music Awards pop idol Justin Bieber was booed by a large section of the audience when he went up to accept the Milestone Award.

Booing? Bieber was dumbfounded, and momentarily speechless before he proceeded to tell the audience that all the other publicity in his life (presumably the recent string of bad PR) should not take away from the fact that he is an artist and this is “all about the music.”

He had a point surely. How many in the music industry have a spotless life. When a Chris Brown is arrested for domestic violence, or an Usher sells out, interrupting his fragrance promotions to be paid a million dollars to perform at a private function for the son of Libya’s ghastly dictator Qaddafi; the music biz tends to look the other way.

So what has Bieber done to upset his fraternity? Surely his recent throwing-up on stage was not the cause. Or the alleged dope smoking. Hello, you’d wipe out the entire industry if that was suddenly a crime. Perhaps what did it was his recent signing of the visitors book at the Ann Frank museum (expressing that had Ann lived, she would surely have been a a Belieber..) surely these things were not especially worthy of booing?

So just now I searched the reactions in the music press and Hollywood media to see what people were talking about. After all, reputation is in the hands of the people. And this time the people had clearly spoken.

So here it is. This is the crime: the thing that earned so much opprobrium. It was Bieber’s lip synching. Here’s an artist who says its “all about the music” and he’s not even singing. To be honest, few others were actually singing at the awards either – judging by comments – but let’s be honest, if you’re a pop idol, manufactured and permed and wardrobed within an inch of your life, the one thing you need to cling on to is credibility. So far in his career Bieber has been able to claim that for all the fad-ism around his image – a modern day Ricky Nelson – he can still actually sing.

Only these days he doesn’t.

One of the keys to reputation – a dimension that enables Madonna to sustain an amazingly long showbiz career is authenticity. Gaga has it. Great artists basically all have it. Deep down these people can write and sing – they’ve got the real stuff.

The same goes for great companies and other organisations. They each have a talent and they work hard to hone this. Levis still makes hard wearing denim. John Deere still makes reliable tractors. Coca-Cola had a shot at changing the formula – but quickly learned it needed to stick to being the real thing. Cola flavoured, sugared water maybe – but it doesn’t pretend to be anything else.

Whatever we do, our reputations rely on the same substance: authenticity. Bieber has just been smacked down by his peers. Mate, we won’t respect you unless you get real.

The lost art of the Apology. Don’t spin it.

A feature of life in the age of social media is that one’s mistakes never actually go away. We saw that this week when a widely published 2006 article with the Abercrombie & Fitch CEO was dragged back, seven years later and used to hit that same CEO around the head. Yesterday he issued an apology for making exclusionist remarks in 2006 about trying to target only the cool kidss.

There were three responses to the apology. In order of ascending size here they are:

1) A retweet – basically saying “yay – he’s finally apologised.” Very few of these.

2) A criticism that the apology was half-hearted at best, and insincere. A few of these.

3) Ignore the apology. Widespread.

In balance you’d have to say that the apology did stuff-all good for the firm. Today there are still masses of protests about the initial remarks and the protest will continue to run on its own momentum for a few more days. It was already slowing down when the apology was published.

My first of two questions are this. Why did a public, so heated about the initial comments, not bother to find, read and retweet the apology? The answer i think is that they didn’t want to. The protest was a chance to vent against a brand they don’t like, and they weren’t interested, actually, in any kind of closure. The hatred circuit remains open.

The second question: why did the apology gain such a tepid critical response from among those few who reported it? Well, let’s dissect the apology. Here it is: the full statement.

“I want to address some of my comments that have been circulating from a 2006 interview. While I believe this 7 year old, resurrected quote has been taken out of context, I sincerely regret that my choice of words was interpreted in a manner that has caused offense. A&F is an aspirational brand that, like most specialty apparel brands, targets its marketing at a particular segment of customers. However, we care about the broader communities in which we operate and are strongly committed to diversity and inclusion. We hire good people who share these values. We are completely opposed to any discrimination, bullying, derogatory characterizations or other anti-social behavior based on race, gender, body type or other individual characteristics.”

The first problem with the apology is the medium. For sure, A&F were getting bagged on Facebook, but this was not where the majority of the conversation was taking place. So the apology was somewhat remote. Metaphorically, no eye contact was made.

The distancing gambit. “While I believe this 7 year old, resurrected quote has been taken out of context…” has all the hallmarks of the distancing strategy. Instead of facing up to criticism the public can here the familiar “I was taken out of context…” line used by politicians all too frequently. The subtext: ‘it wasn’t me…don’t blame me.” This is not the gutsy, “okay, I screwed up” mea culpa that people are asking for.

“I sincerely regret my choice of words…” More distancing. He in no way regrets his sentiment, that he wants his brand to be worn only by skinny cool kids. So he tries re-framing that objective as “…we’ve always had an aspirational brand.”

Finally he turns up the national anthem and pledges his allegiance to our shared values. “…we care about the broader communities in which we operate and are strongly committed to diversity…” This comes over as insincere simply because he was so blunt in the first place about his target market.

Now this blog didn’t set out to attack the CEO. Rather, I wanted a typical exampled of a failed apology. For surely to apologise and be met with 87% utter silence, 10% derision and 3% acceptance (my estimates based on twitter traffic) is not a successful PR move. Rather than cut a firewall through the blazing criticism, the apology has merely thrown a damp sponge at the heart of the fire.

In my view it would have been better NOT to apologise if, as it seems, the firm is intractably committed to serving the young, the skinny and the beautiful.

But if an apology is on offer – and it wants to assuage the public thirst for blood – then it needs to follow certain rules.

Never ruin an apology with an excuse.

― Benjamin FranklinNixon’s grand mistake was his failure to understand that Americans are forgiving, and if he had admitted error early and apologized to the country, he would have escaped.

– Bob Woodward

These two quotes sum up the essence of a good credible apology. It should come quickly and be offered without qualification. If you’re sorry, then be sorry – don’t process the apology, don’t spin it, or try and mitigate the thing you did wrong. Every single step that you take to minimise the pain, or distance yourself from it, or to wriggle out of culpability is going to be spotted immediately as insincerity.

Here are four things to avoid.

- Distancing. Either through tone (third person..”mistakes were made, people may have been hurt…”) or through blaming others. “In our group’s exuberance, some of us got carried away…” (Blame the group.)

- Attack those hurt. “I’m sorry if some of you took offense at my joke…”

- Deflection. Apologising in advance (“I apologise if any of you get offended by my next statement about women…” or apologising for something else: “I’m sorry for the hurt I did to that child…if I’m guilty, then it’s guilty of enjoying boisterous play.”

- Abbreviated Apologies – used in the context of other statements. “I hurt people and I apologise…but I’d like to restate my commitment to seeking the truth.” Blink and you miss these.

At the heart of the decision to apologise – or not – is the issue of courage. You either have the courage to do things that offend others (presumably to serve a greater good,) or you have the courage to admit you were wrong. Today’s plethora of half-hearted apologies try to straddle both, and end up failing to do their job.

A good apology should simply be honest. Don’t delay it, or spin it.

Abercrombie & Fitch – a reputational glitch

Since the 1990s Abercrombie & Fitch has been a fashion brand that has taken the label from failure (it harks back to 1892 but by the 70s had failed as a company,) to gigantic success with an annual turnover measured now in the billions. At the heart of this story has been a fundamental disconnect between the image of the brand – clean-cut, Mid-Western, Joe College values (exemplified by their use of the Carlson twins as models who showed off their flesh more than they did the actual fashion) – and the aggressive multinational fashion company that uses cheap third world labour to manufacture faux nostalgia (college sweatshirts that you might have rescued from your dad’s top drawer) and then peddle this through a lavish chain of upmarket flagship stores.

Since the 1990s Abercrombie & Fitch has been a fashion brand that has taken the label from failure (it harks back to 1892 but by the 70s had failed as a company,) to gigantic success with an annual turnover measured now in the billions. At the heart of this story has been a fundamental disconnect between the image of the brand – clean-cut, Mid-Western, Joe College values (exemplified by their use of the Carlson twins as models who showed off their flesh more than they did the actual fashion) – and the aggressive multinational fashion company that uses cheap third world labour to manufacture faux nostalgia (college sweatshirts that you might have rescued from your dad’s top drawer) and then peddle this through a lavish chain of upmarket flagship stores.

A&F deliver dreams. They’re not alone in this, far from it, and in many respects they exemplify A+ marketing: tapping into needs and wants and through packaging, price and placement ensuring healthy profits.

But the disconnect comes at a price. Reputational Risk. It is one thing to be a brand that, deep down, offers a perfromance benefit. For some reason I’m thinking of Coleman and camping supplies. That company has been dedicated to delivering products that function, and show little details that users appreciate. A fashion label such as A&F simply delivers image. Its product quality is nothing special, it’s designs are derivative rather than original, it’s fabrics – mostly cotton – offer no USP. But the dreams and packaging and catalogues and image – well, they’ve been the reason for the brand’s success. It sells something that is accessible. You too can be part of the A&F movie. One of the gang.

But it turns out the gang is less inclusive than it has made out in the advertising. The CEO is quoted as saying that he doesn’t want to sell larger sized items because he doesn’t want fat people wearing his brand. He doesn’t want them in his stores. Instead of being genial Joe College, Abercrombie & Fitch is, deep down, the spoilt snob.

Suddenly the gap between image and reality is made, in just one quote from the CEO, as plain as day. Here’s what happend. I’m taking this straight from The Drum.

An LA-based writer is looking to give Abercrombie & Fitch a ‘brand readjustment’ by asking viewers to donate their A&F clothing to their local homeless shelter, after the CEO of the company suggested he didn’t want ‘unattractive people’ or people over a certain size shopping there.

Greg Karber created a YouTube video suggesting that people donate clothes, and send pictures of them doing so to #FitchTheHomeless.

The video went live on Monday and has so far almost received a million views.

In it, Karber insists ‘Together, we can remake the A&F brand.’

The video caught like wildfire – with more than a million “likes” on Facebook within 48 hours. With the story being widely picked-up in the media this week the twittersphere has become a pile-on of latent A&F hate. The story in itself has resonance, but I suspect the speed at which this reputational wildfire has spread comes from the degree to which the brand has already built up enmity within the public.

- Everyone loves the A&Fitch bashing video. The brand is for 14 yr old douche bags anyways, it doesn’t need a homeless ppl “readjustment”

- Abercrombie & Fitch would rather burn the clothes that it doesn’t need rather than give it to charities… Wow.. Um… Ya…

- I’ve been hating on Abercrombie & Fitch for years, just because their clothes are ugly, y’all slow

There are at least 4 solid reputation management lessons to be drawn from the story so far.

- The wider the gap between your image and your reality, the bigger the reputation risk.

- Over time every little misstep or poor judgement will aggregate to form a parallel narrative to your official version. Like debris in a forest, it will prove flammable in certain conditions.

- Every once in a while it pays to cut some clean firebreaks through bold, well intentioned actions that are both credible and meaningful.

- You may stand FOR something, and FOR your target market. But don’t confuse that with the making statements that put down others. Remember, they are legion and they are armed with social media.

For his own part, film maker Greg Karber may face a firestorm of his own. I’m predicting he will on the basis that he has also ignored three of the four rules above. He has not validated his expertise on the subject of ethics – and judging by his whining, even sarcastic tone in the video – he seems more personally aggrieved than truly concerned with business ethics. I might be wrong there, but he leaves room for doubt.

But already there has been growing criticism of his use of homeless people as mere props in his production. Never once does he seek their opinion, or lend them much dignity either. His message: since A&F hates the uncool – I’ll use the uncool to highlight the fact. In so doing he’s just as guilty of snobbery as is his target.

There’s a fifth lesson in reputation management that karber should heed. Most reputational damage is self inflicted.

Great video – George Carlin on the language of politicians

“An ‘initiative’ is an idea that’s not going anywhere…” Excellent video that is both truthful and entertaining. The great George Carlin gives a talk to the Press. Brilliant.

Why we need the Aaron Gilmore story

Media in my country, NZ, have been having a field day with the story of MP Aaron Gilmore who is a lowly ranked politician yet, apparently, quite puffed up in terms of his ego. He has popularised a saying “Do you know who I am??” to the point that I’d bet good money that it will appear on a t-shirt before the end of the month.

In this case he used the phrase when shouting at a waiter who had wisely refused to serve the MP any more alcohol. Gilmore threatened to have the waiter sacked, and stated more or less that all he had to do was call the Prime Minister’s office and make it happen. In embarrassment Gilmore’s own friends marked the occasion by leaving the restaurant or, in the case of a lawyer friend, apologising to the restaurant.

Gilmore, must have seen the error in his ways, because next day he issued a powerful apology of his own. Powerful? get this:

- It was on Twitter rather than in person.

- It tried to frame the rowdy behaviour as coming from his group – rather than from himself. Eye witnesses said there was only one loudmouth in the room.

- It used the weasel language we’ve all come to loathe: “I apologise if for any reason anyone may have taken offence…” (See the George Carlin video on political language.)

In other words not an apology at all. It incensed the lawyer friend enough that he went to the media with the story.

On the scale of things, Gilmore’s vile behaviour (he later admitted that he’d had one and a half bottles of wine) is small potatoes. The man has been shamed to the point that he’s closed his FB and Twitter accounts, and for the rest of us, the world will keep on spinning.

For me the interesting thing is why these small stories – of stars and leaders – seem to be such rich targets for the public conversation. Why do they become trending topics when they are really so small?

The answer can be explained by the great American sociologist Robert Merton who caused a stir in the early 1950s when he suggested that criminals, while not to be encouraged, actually do society a favour by acting out a passion play in which sin is duly found out and punished. These dramas get tut-tutted by the community and help us affirm acceptable versus unacceptable behaviours.

This is part of the dynamics surrounding reputation. Reputation isn’t just about what people do, but about their motivations for taking their actions. We’ll accept that somebody might get drunk at a restaurant – it is hardly newsworthy. But it does become newsworthy when that person is an MP and he puts his venal pride on display. Did Gilmore in his intoxicated state reveal his deep sense of humanity?

We expect of MPs at least a show of public service. Gilmore didn’t bother with that – he simply demonstrated through words and actions what a jumped-up, self-interested prat he could be.

Now it takes more than Gilmore’s actions to get into the headlines. What gave the story traction was the public’s underlying concern that all MPs might be like this. In other words the Aaron Gilmore story was just the proof we were already looking for. His actions fitted like a glove with our worst fears.

I keep returning to this lesson. Reputation depends on three things. What you do. What your real motivations are – are they good and true? Are your motivations in sync with the public agenda.

Aaron Gilmore (“regalia moron” said one acronym posted on Twitter) did us all a favour. He kept alive our latent cynicism, and his boorish behaviour will ensure that from now on, we’ll all know who he is.

Ethical test. Where do you stand?

Today I came across this TVC which has had a quarter million hits. It is a German production – and the headline on the newspaper means something like Fugitive. Clever stunt? Or does it cross the line? Press this link to go to recent TVC – ethical or simply clever?